This past year, while reading migration narratives, instead of writing critical essays analyzing the texts, I had my students create adaptations of the text for another medium. To adapt a text, students must master both the content and the literary elements used in the source material to be able to meaningfully represent its message in the alternative medium. At the same time, students are encouraged to develop skills for using additional, contemporary communication techniques.

Educator Tip: My students adapted text into comic books, but the same approach might be used for adaptations from text into other mixed media such as slide shows or videos that might also incorporate sound. Consideration should also be given to accessibility and allowing audio only adaptions such as radio plays or podcasts that incorporate sound effects and a musical score.

The process challenges students with a range of complex tasks, including:

- Deciding what text to keep,

- Translating text into sequential art,

- Storyboarding the narrative to convey tension and mood through transitions and panel composition, and

- Deciding how to generate a human connection between the characters and readers.

Those tasks were made more challenging for both my students and me because our process needed to incorporate 100% distant learners with students on alternating hybrid learning schedules.

We broke the process into a series of steps.

- Selecting the most relevant material.

- Identifying and categorizing what needs to be communicated.

- Scripting and thumbnails.

- Drawing and lettering.

- Sharing and evaluating.

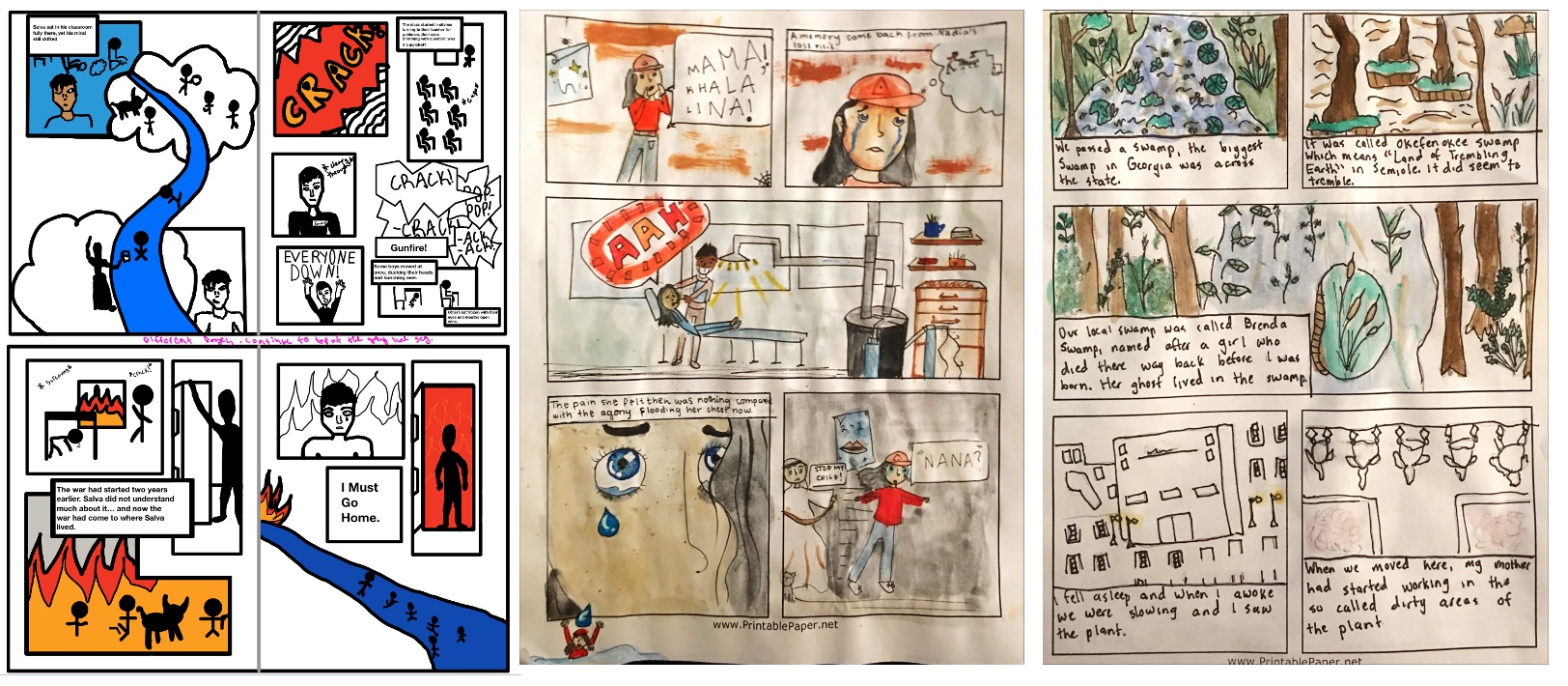

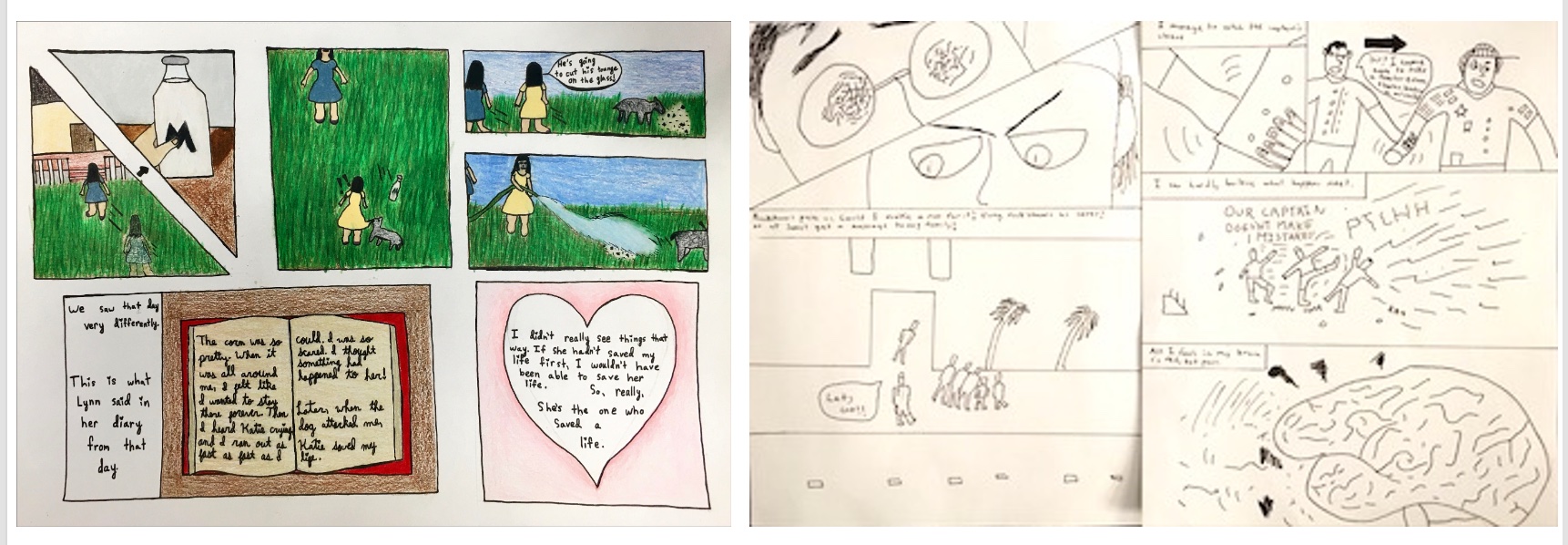

The first step in the process required students to focus on a key chapter in the text. For some students, it was the climax of the novel. Other students selected chapters that reveal the horrible circumstances driving the characters to leave their homes. Still, others chose the resolution to show the characters’ deep sense of hope and resilience. Students communicated why they selected the chapter and what they hoped to convey through a comic adaptation as part of their selection process. Identifying the “why” helped shaped their approach to the transformation.

Next, students had to drill down into the mechanics of that section of the narrative. They used highlighters to color-code vital pieces of text (captions), internal and external dialogue (balloons), and key symbols, images, or descriptions (art). These annotations guide the scripting process. Some students experienced “Aha!” moments during the annotation process. More concrete thinkers began to “see” the story and characters in more vivid and complex ways. They were able to create a movie in their heads of what they were reading. Before moving on to the scripting step, I asked students to reflect on what key information is missing that their reader might need to know (e.g., for Bamboo People, readers might benefit from a map of Myanmar at the beginning of the adaptation).

Next, students had to drill down into the mechanics of that section of the narrative. They used highlighters to color-code vital pieces of text (captions), internal and external dialogue (balloons), and key symbols, images, or descriptions (art). These annotations guide the scripting process. Some students experienced “Aha!” moments during the annotation process. More concrete thinkers began to “see” the story and characters in more vivid and complex ways. They were able to create a movie in their heads of what they were reading. Before moving on to the scripting step, I asked students to reflect on what key information is missing that their reader might need to know (e.g., for Bamboo People, readers might benefit from a map of Myanmar at the beginning of the adaptation).

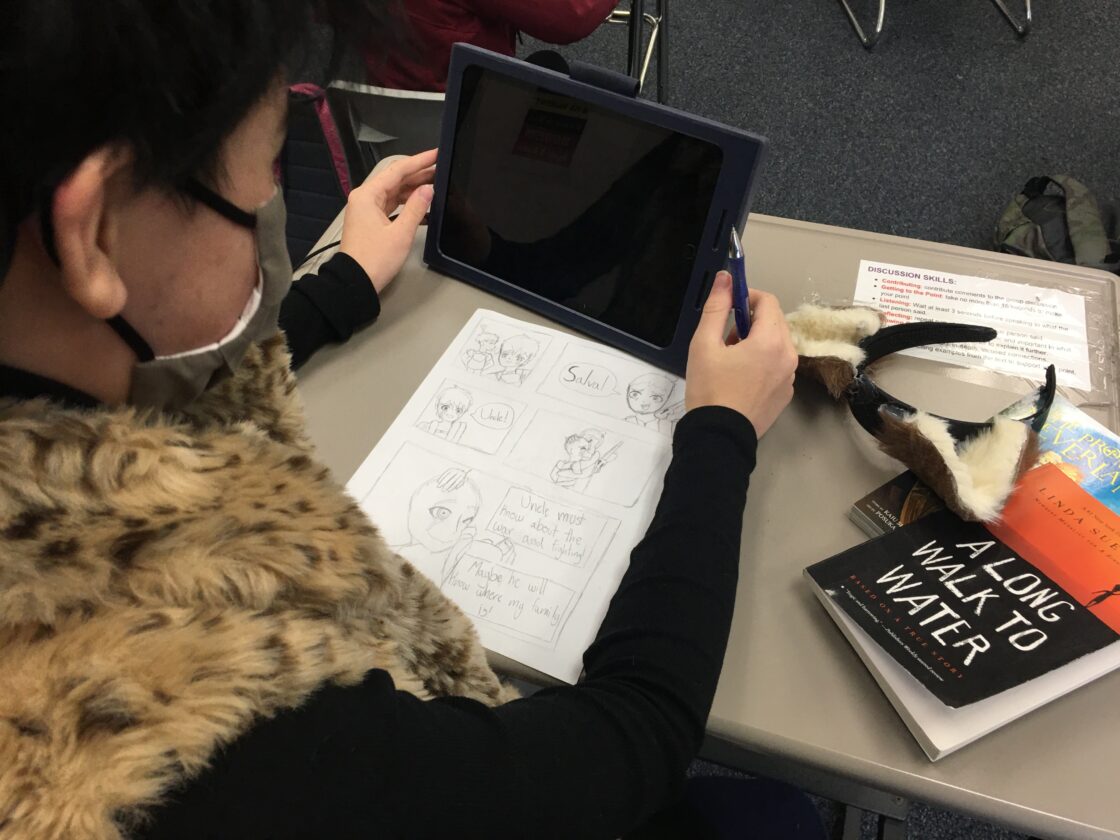

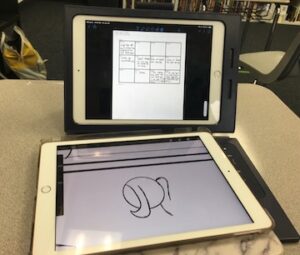

For scripting and thumbnails, I showed students two different approaches.

The second approach was more traditional and used a three-row script template that included cells for narration, action, and dialogue for each panel.

I created samples of each method and allowed students to self-select.

Once students had developed scripts, they move on to the drawing and lettering phase. Classroom supplies included blank paper; a link for blank comics layout templates; pencils; erasers; rulers; thin, black permanent markers; watercolor paints; etc. Around the classroom, I set out physical editions of various comics-making resources for students to reference. At the front of the classroom, I displayed three copies of Comics: As Easy as ABC by Ivan Brunetti.

Once students had developed scripts, they move on to the drawing and lettering phase. Classroom supplies included blank paper; a link for blank comics layout templates; pencils; erasers; rulers; thin, black permanent markers; watercolor paints; etc. Around the classroom, I set out physical editions of various comics-making resources for students to reference. At the front of the classroom, I displayed three copies of Comics: As Easy as ABC by Ivan Brunetti.

Educator Tip: Brunetti’s book is the most comprehensive and yet accessible comics-making resource for middle and younger classrooms. I separated the pages, laminated them, and kept each copy on a ring to keep them organized. Separating the pages allowed students to take the page they needed to their desk, thereby allowing more students to access the rest of the pages. Having the pages laminated not only protects the pages but enables students to trace over Brunetti’s images with wet-erase markers for practice.

Completed comic book adaptations were displayed in the classroom to allow for sharing. Even though I could not use some of the sharing exercises I have typically drawn upon because of the school’s social distancing and public health protocols for a pandemic, we still created an audience for the students’ work. Next year, I look forward to table discussions around the decision-making process and offering a wider variety of materials.

Here are a few of this year’s sample pages.

.

Lesson Learned: In the future, I would not allow students to use pixton.com for this project because of the nature of the images and the lack of representation, especially for migration narratives. I also observed that the adaptations created using Pixton employed less creative use of color, imagery, and layouts.